Swinging the club past parallel isn't just a style issue, it's a common cause of inconsistent strikes and a frustrating loss of true power. When the club head drops down past that point where the shaft is parallel to the ground, it forces a complex series of compensations on the way down just to find the ball. This guide will walk you through exactly why it happens and provide actionable drills to train a shorter, more powerful, and far more consistent backswing.

What "Past Parallel" Means (And Why It Robs You of Consistency)

Let's get on the same page with the terminology. At the top of an ideal backswing, the golf shaft should be, at its maximum, parallel to the ground and pointing more or less down your target line. "Past parallel" is any swing where the club dips below that point, often pointing well to the right of the target for a right-handed golfer.

You might think a longer arc equals a faster downswing, but it's not that simple. When you go past parallel, you usually sacrifice structure and connection. Here's the fallout:

- Loss of Sync: Your arms and body, which worked together on the way up, become disconnected. The body starts the downswing while the arms are still finishing their long journey, forcing a frantic "catch up" motion.

- Rerouting is Required: From a past-parallel position, the club cannot simply drop into the correct delivery slot. You have to reroute it, often by casting it over the top, leading to pulls and slices.

- Inconsistent Contact: With all that extra movement and necessary rerouting, your swing bottom becomes a moving target. Some shots are thin, some are fat, and solid contact feels like a lucky coincidence.

The goal is not to have the shortest swing, but to have a swing that is the most efficient. A shorter, more connected swing is almost always more powerful and repeatable than a long, loose one.

The Real Reasons You're Overswinging

Most golfers don't intentionally swing past parallel. It’s an effect, not a cause. It's your body's attempt to complete a backswing when something else in the sequence has gone wrong. Let's look at the most common culprits.

A Poor Turn Forces the Arms to Take Over

This is the number one cause. Many amateur golfers have a backswing that is dominated by their arms and hands, with very little rotation from their torso and hips. When your body stops turning prematurely, but you feel like you aren't at the "top" yet, your arms will continue to lift and fold independently. This collapses the entire structure. The hands get high, the trail elbow bends excessively, and the club's momentum carries it helplessly past parallel.

A proper backswing should feel like your arms stop moving when your shoulders stop turning. If your turn is cut short, your arms shouldn't try to make up for it.

The Disconnected Lift in the Hunt for Power

There's a prevailing myth in golf that a bigger swing automatically creates more speed. In pursuit of hitting the ball farther, many players will consciously try to take the club back as far as possible. This intention often backfires, transforming a rotational swing into a vertical lift. When you think "long," you often just lift your arms straight up away from your chest. That lifting motion detaches the arms from the engine of the swing - your torso - and results in a long, weak, and narrow position at the top.

True power comes from width and rotation, not from simply lifting the club as high as you can.

A Collapsed Lead Arm or Flying Trail Elbow

Structure at the top is everything. For a right-handed golfer, structure is often ruined by one of two related faults:

- The Bent Left Arm: When your lead arm (left arm for RH golfers) breaks down and bends significantly at the elbow, it’s like a support beam being removed. There is nothing to stop the club from collapsing across the line and dropping past parallel.

- The Flying Right Elbow: When the trail elbow (right arm) doesn't stay relatively pointed towards the ground and instead "flies" out behind you, it pushes the club across the line and encourages a disconnection between the arms and the body turn. This often goes hand-in-hand with an overswing.

Lack of Physical Awareness (Proprioception)

For golfers who are naturally very flexible, sometimes you just can't feel where the club is in space. Your shoulders are still turning, your arms are still flexible, and your body doesn't send the "stop" signal until it's way too late. It doesn’t feel long to you, but a camera would show the club dipping way below parallel. For these players, drills that provide external physical feedback are incredibly effective.

Four Drills to Shorten Your Backswing and Gain Control

Understanding the problem is one thing, feeling the solution is another. These drills are designed to retrain your body and give you the feeling of a connected, compact, and powerful top-of-swing position.

Drill 1: The Headcover Tuck

This classic drill is maybe the best one ever for teaching arm-body connection and preventing the arms from working independently.

- Take your normal setup.

- Tuck a golf headcover (or a small towel) into your trail armpit (the right armpit for a right-hander).

- Make small backswings with the goal of keeping the headcover pinned between your arm and your chest.

- Gradually make your swings bigger until you can make a full, three-quarter turn without the headcover dropping. If it falls, your arm has lifted away from your body.

This will almost instantly show you the limit of your connected turn. It might feel "short," but it's likely where your efficient and powerful swing should be finishing.

Drill 2: The Right-Shoulder Stop

This drill helps you feel precisely where a full shoulder turn ends, which is the natural end of a connected backswing.

- Take your setup posture without a club.

- Now, grab a club with only your lead hand (left for RH golfers).

- Simulate your backswing, turning your shoulders fully.

- Stop your swing when your lead hand is directly above your trail shoulder (your right shoulder).

From this position, with just one arm, it feels natural and strong. Try to swing farther and you'll immediately lose balance and structure. Now you have a reference point for what a complete, but not overly long, backswing feels like.

Drill 3: The Feet-Together Drill

Overswinging often involves a lot of excess body motion, like swaying off the ball. This drill removes that possibility and forces you to stay centered while you rotate.

- Take your normal address position with an iron, but slide your feet together until they are touching.

- Take smooth, 50-70% swings, focused on just clipping the grass or even hitting a ball teed low.

- If you sway or try to make a long, lifting backswing, you will immediately lose your balance.

This drill teaches you to rotate around a fixed point (your spine), which is the foundation of a consistent swing. You physically cannot overswing and stay balanced with your feet together.

Drill 4: Back Against the Wall

This is the perfect drill for players who lack the physical awareness to know their swing is too long. It provides immediate, undeniable feedback.

- Get into your golf posture a few inches away from a wall, so your back is facing the wall.

- Make a slow-motion practice backswing.

- The moment your club touches the wall behind you, you’ve gone too far.

Adjust your starting distance from the wall until you can make a full shoulder turn and have the club head stop just before it makes contact. This will graphically and physically recalibrate your sense of where the top of the swing is.

Final Thoughts

Reining in an overswing is not about forcefully restricting your motion, it's about replacing an inefficient "lift" with a powerful and connected body "turn." By improving your body rotation and maintaining the connection between your arms and your chest, you'll naturally create a more compact swing that stays on plane and is far easier to repeat, delivering more power with significantly less effort.

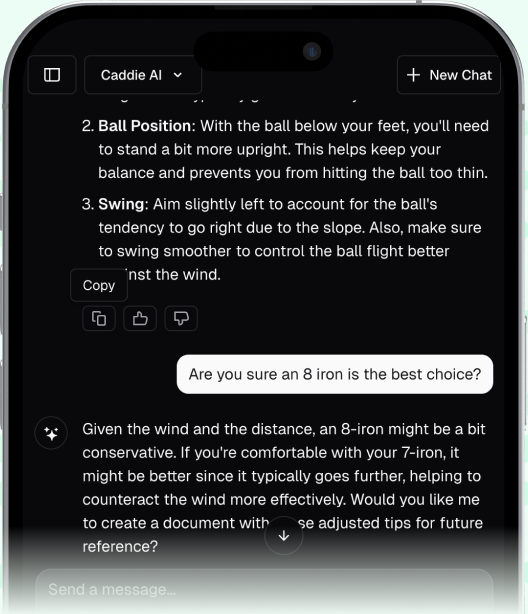

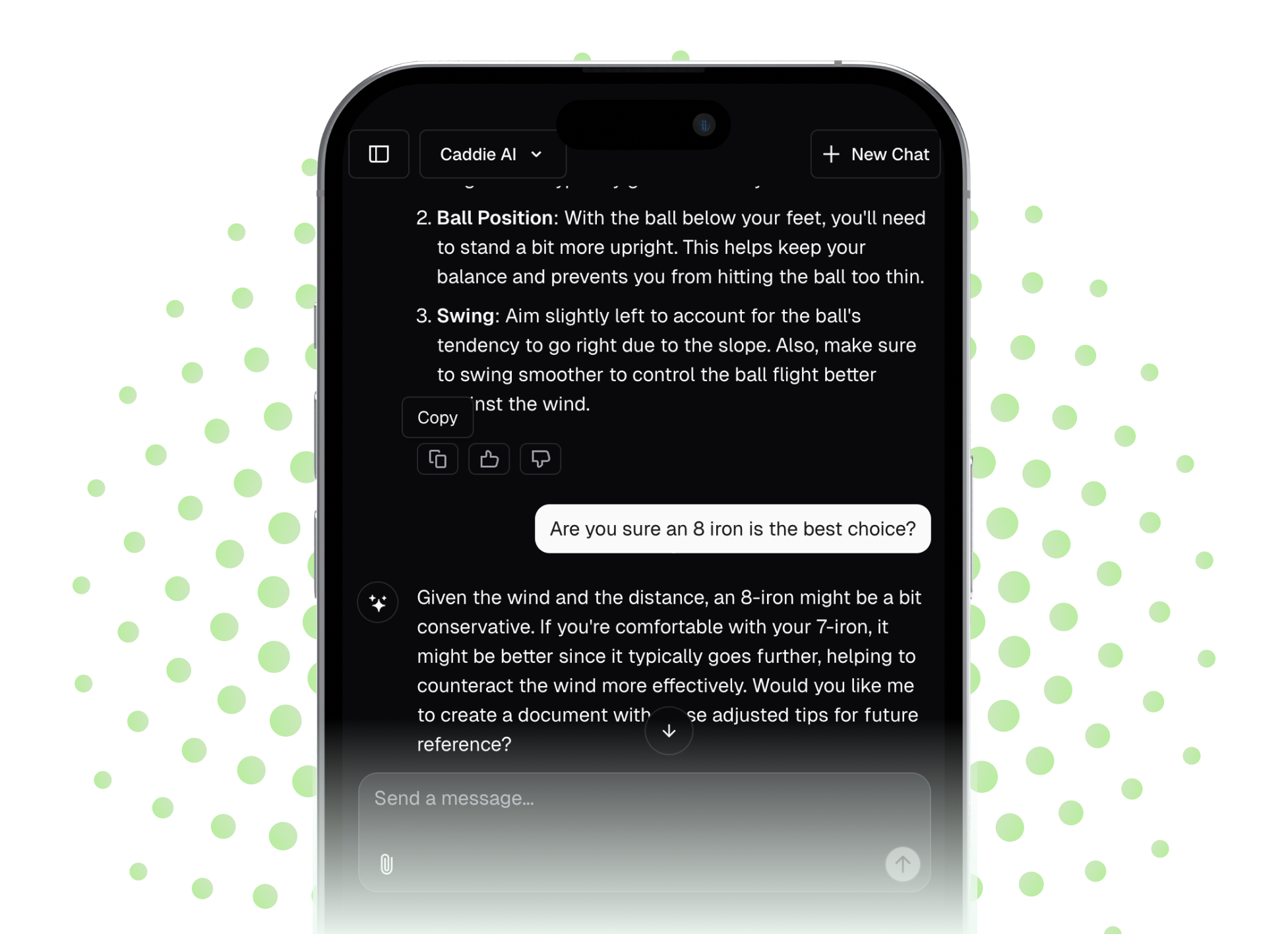

For more personalized guidance on your swing, we also built Caddie AI to act as a 24/7 golf coach right in your pocket. If you are ever at the range wondering, "Am I still going past parallel?" you can get instant feedback. We designed it to take the guesswork out of your practice, providing tailored advice and a way to answer those simple questions you have without having to wait for your next formal lesson.