The indentations on a modern golf ball are called dimples, and they completely transform how the ball flies through the air. Understanding the simple yet brilliant science behind these little scoops is a big step in understanding why your golf shots do what they do. This guide will explain precisely what dimples are, how they work to make the ball fly farther and higher, and what this all means for your game on the course.

It's Dimples, Not Divots: Clearing Up the Confusion

First things first, let's clear up a common point of confusion among new players. The marks you take out of the grass with your club are called divots. The indentations covering the surface of the golf ball are called dimples. It’s an easy mistake to mix them up, and every single experienced golfer has made similar slip-ups when they were starting out. The goal here isn't to get bogged down in terminology, but to feel more comfortable and confident with the language of the game.

Think of it like this:

- Divot: Part of the course. It's the physical evidence on the ground that you made a great, compressed strike (or maybe a not-so-great one!). It tells a story about your swing path and angle of attack.

- Dimple: Part of the ball. It's the functional design that dictates how that ball travels through the air after a great strike.

Once you separate those two terms in your mind, you're already thinking more like a seasoned player. Now, let’s get into the incredible reason those little dimples are there in the first place.

Why Do Golf Balls Have Dimples? The Simple Science of Flight

If you gave a non-golfer a smooth ball and a dimpled ball and asked which would fly farther, nearly everyone would pick the smooth one. It just looks more streamlined. But in reality, a smooth golf ball hit by a top pro would travel less than half the distance of a dimpled ball. Those little craters are a masterclass in aerodynamics.

To grasp why, we need to talk about two things that slow a ball down in the air: drag and lift. The story of the dimple is the story of maximizing one and minimizing the other.

The Old Days: An Accidental Discovery

Early golf was played with smooth, leather-covered balls stuffed with feathers ("featheries"), and later, solid balls made from the sap of the gutta-percha tree ("guttas"). For a long time, golfers accepted that smooth spheres were the way to go. But they noticed something peculiar: their older, beat-up "gutta" balls, which were covered in nicks and scuffs from use, consistently flew farther than brand-new, perfectly smooth ones. Canny players and ball-makers eventually started intentionally adding patterns to the balls, which ultimately evolved into the modern dimple we know today.

Fighting the Drag

When any object, like a golf ball, moves through the air, it creates resistance. This is called aerodynamic drag. On a smooth ball, the air flows cleanly over the front but struggles to stay attached to the curved surface on the back. This causes the air to separate from the ball early, creating a large, chaotic patch of low-pressure air behind it, known as a wake.

Imagine a barge pushing through water - it leaves a huge, turbulent wake behind it. This large wake sucks backward on the smooth ball, causing immense drag (specifically, something called "pressure drag").

This is where the magic of the dimple comes in. Each little dimple creates a tiny bit of turbulence. All these little pockets of turbulence combine to create a very thin layer of choppy air that "hugs" the surface of the golf ball. Because this turbulent layer has more energy, it can cling to the back of the ball for much longer before separating. The result? A much smaller, less chaotic wake behind the ball.

Even though the dimples add a little bit of surface friction, the massive reduction in the backward-sucking pressure drag is so significant that it allows the ball to cut through the air far more efficiently. A dimpled ball's total drag is about half a smooth ball's.

The Second Secret: How Dimples Create Lift

Dimples do more than just slash drag, they are also essential for generating lift, which is what keeps the ball in the air for so long, turning short line drives into majestic, hanging drives.

This part of the process relies on another key element of a good golf swing: backspin. When you strike down on a golf ball properly with an iron, the club’s loft imparts significant backspin on the ball.

The Magnus Effect at Work

As the ball soars through the air while spinning backward, its surface interacts with the oncoming air.

- The air flowing over the top of the ball is going in the opposite direction of the ball's spin. This slows the air down relative to the ball's surface.

- The air flowing underneath the bottom of the ball is going in the same direction as the ball's spin. This speeds the air up relative to the ball's surface.

According to a fundamental law of physics called Bernoulli's Principle, faster-moving air has lower pressure, and slower-moving air has higher pressure. This creates a pressure imbalance: there is now higher pressure pushing up from underneath the ball and lower pressure on top. This pressure difference creates an upward force. In golf, we call this aerodynamic lift.

Dimples greatly enhance this effect. By helping that chaotic layer of air "stick" to the ball's surface, they make the interaction between the spinning surface and the air more pronounced, supercharging the Magnus effect and producing more lift than would be possible on a smooth, spinning ball.

So, to put it all together: Striking the ball well generates backspin. That backspin, combined with the dimples, creates lift. That lift keeps your ball in the air longer for maximum carry distance.

Are All Dimple Patterns the Same?

No, not even close. Golf ball manufacturers pour millions of dollars into research and development to create unique and proprietary dimple patterns. Varying the number, size, shape, and arrangement of dimples can dramatically alter a ball's flight characteristics. Most golf balls have between 300 and 500 dimples.

Here’s what engineers are playing with:

- Dimple Number and Coverage: Some designs use hexagonal or other non-circular dimples. The logic here is that shapes like hexagons can be tiled together more efficiently, leaving less flat, non-dimpled space on the ball's surface. More total dimpled area can lead to more consistent aerodynamics.

- Depth and Shape: Shallower dimples tend to create a lower, more piercing ball flight by reducing lift. Deeper dimples can increase lift for a higher trajectory. Many manufacturers now use a "dimple-in-dimple" design or a mix of different sizes and depths on the same ball to optimize flight throughout the entire journey - from leaving the clubface at high speed to slowing down at its apex.

- Symmetry and Pattern: Today’s patterns are far from random. They are meticulously designed into symmetrical, repeating geometric patterns (often based on shapes like an icosahedron or octahedron) to ensure the ball flies consistently regardless of how it's oriented on the tee or in the air.

A golf ball designed for high-performance players who generate a lot of spin might have a pattern engineered to produce a slightly lower, more controllable trajectory. On the other hand, a ball marketed to average golfers who need more distance might have a pattern designed to maximize lift to help weaker shots stay airborne longer.

The Player's Takeaway: What This All Means for You

You don't need to be an aerospace engineer to play good golf, but understanding these principles provides some practical, on-course benefits.

1. A Clean Ball is a Long Ball

Now you know why tour pros and their caddies are so diligent about cleaning the ball before every single shot. If the dimples are filled with mud, sand, or a glob of grass, the aerodynamics are completely disrupted. The ball won't fly as far, a lot of lift will be lost, and the flight can become unpredictably wobbly. Always take a moment to clean your ball on the tee and before you putt. It’s one of the easiest ways to ensure you get the predictable performance you pay for.

2. Understand the Ball You're Playing

Recognize that balls are designed differently for a reason. If you struggle to get the ball in the air, choosing a "distance" or "soft feel" ball with a dimple pattern designed to enhance lift can legitimately help you gain carry yardage. If you're a high-spin player looking for more control in the wind, a "tour" ball with a dimple pattern for a lower flight might be the better choice.

3. Connect Your Divot to Your Dimples

Finally, let's tie the two terms back together. The quality of your divot (the slice of turf) is directly related to the quality of the strike. A good divot - starting just after the ball and pointing towards your target - is evidence that you’ve hit down with a descending angle of attack. This creates the compression and backspin needed to activate your ball’s dimples and generate the drag-reducing, lift-producing flight that sends the ball soaring properly.

Final Thoughts

In short, the small indentations on a golf ball are called dimples, and their complex design is fundamental to how far and consistently a ball can fly. By creating a thin turbulent boundary layer, they dramatically reduce drag and work with backspin to generate a lifting force, all of which results in longer, more stable golf shots.

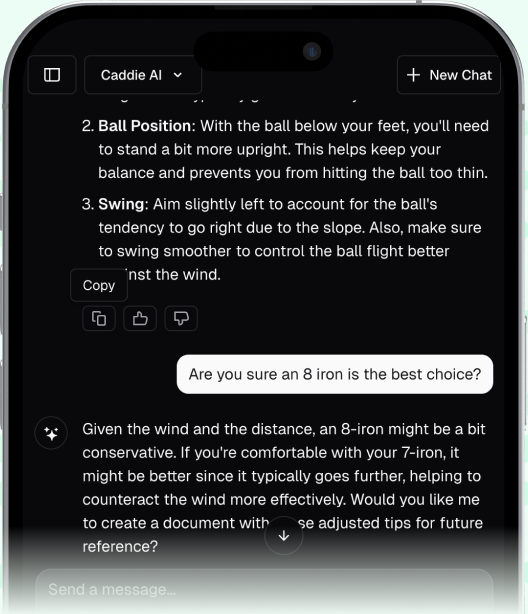

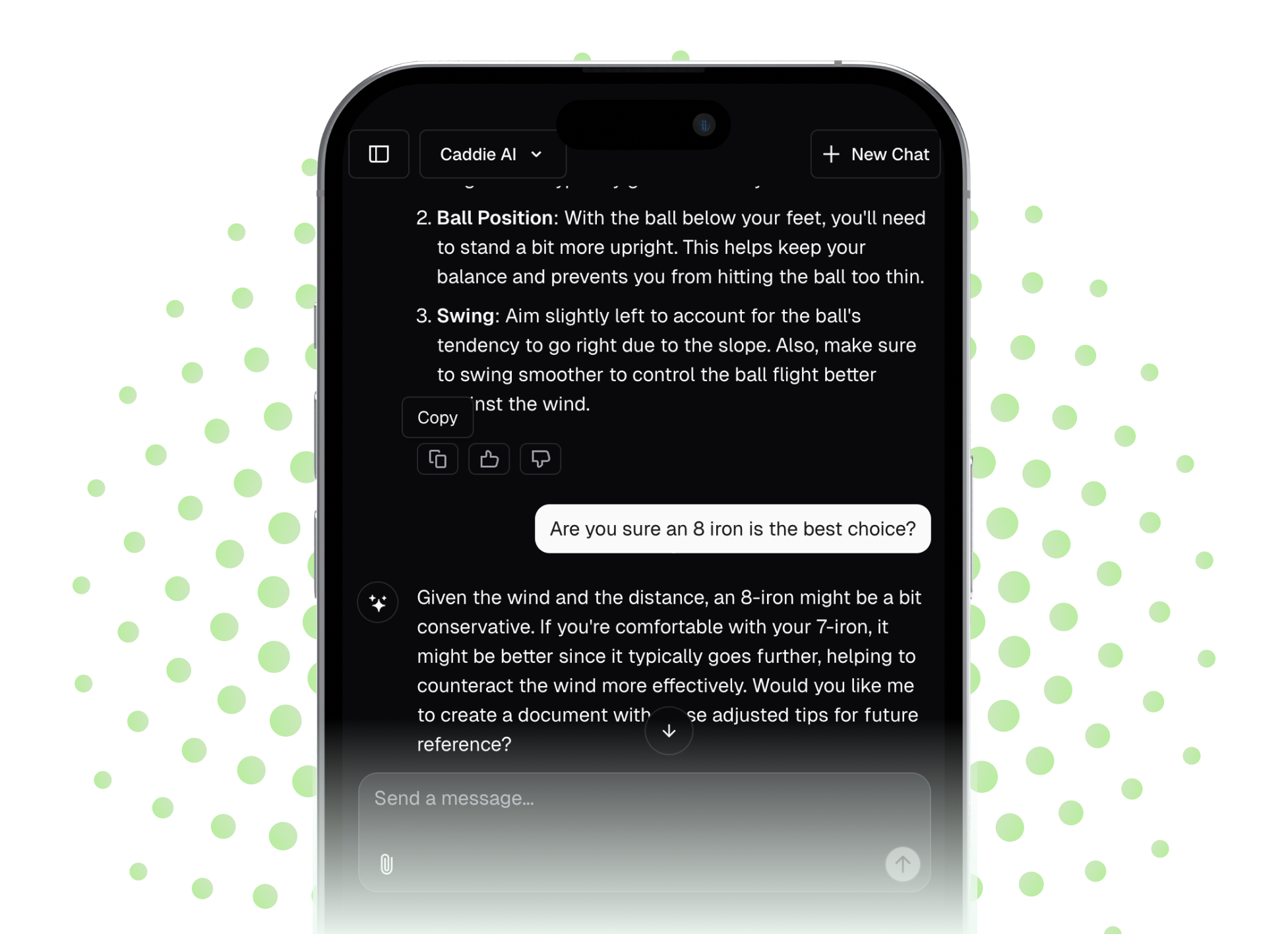

Knowing the "why" behind equipment is part of the fun, but on the course, you just want to know "how" to hit the best shot. We love helping golfers make smarter decisions and play with more confidence, which is why Caddie AI is designed to translate all this complexity into simple, actionable advice. Instead of trying to calculate lift and drag coefficients in your head, you can get instant guidance on club selection and shot strategy, ensuring you play the right shot that takes full advantage of your ball’s technology in any situation.