That perfect, bacon-strip divot you see pros take after a pure iron shot isn't an accident - it's the direct result of a fundamentally sound golf swing. It's the physical evidence that they compressed the ball correctly. This article will show you exactly why divots happen, what they tell you about your swing, and provide a clear plan to start making proper contact yourself.

The Truth Behind the Turf: What is a Divot, Really?

First, let's clear up the single biggest misunderstanding about divots: A good divot is taken after the ball has been struck, not before. Many golfers believe they need to dig down and scoop under the ball to make it go up, leading them to hit the ground first. This is the cause of "fat" shots where the club digs into the turf behind the ball, loses all its speed, and sends the ball dribbling forward.

Think of it like a chef slicing a carrot on a cutting board. The sharp knife hits the carrot first, slicing cleanly through it before making contact with the cutting board underneath. In this scenario:

- Your clubface is the knife.

- The golf ball is the carrot.

- The turf is the cutting board.

The goal is to strike the golf ball first with a downward motion. The club continues on its arc, bottoms out just after the ball, and takes a shallow slice of turf - the divot - in the process. That's it. It’s a consequence of a good swing, not the goal itself.

The Science of a Sweet Spot: Hitting Down to Make the Ball Go Up

It sounds counterintuitive, but hitting down on the ball is what makes it go up into the air with an iron. This all comes down to two concepts: "low point" and "attack angle."

Understanding Your Swing Looping Point, AKA Low Point

Every golf swing moves in an arc or a circle around your body. The "low point" is the very bottom of that arc, the point where the clubhead is closest to the ground. For a great iron shot, this low point must happen after the ball. When your low point is positioned correctly, you get that "ball-then-turf" contact that feels so solid.

If your low point is behind the ball, you’ll hit the ground first (a fat shot). If your low point is too high and just barely grazes the ball, you’ll hit it "thin," causing it to scream low across the ground.

Unwinding with a Proper Attack Angle

Attack angle is simply the direction the clubhead is traveling - up, down, or level - as it approaches the ball. For irons, you want a negative attack angle, meaning the club is still moving downward on its arc at the moment of impact. This is what allows you to "compress" the golf ball.

When the club strikes the ball on a downward path, it squishes the ball against the clubface for a fraction of a second. This compression, combined with the loft of the club, generates the backspin that causes the ball to climb into the air and ideally stop quickly on the green. Trying to "help" the ball into the air by scooping or lifting ultimately robs you of power and spin, leading to inconsistent contact and poor shots.

Reading the Tea Leaves: A Player's Guide to Interpreting Divot Patterns, from Bacon Strips to Catastrophes

A round of golf may feel like an unsolvable riddle sometimes. But not when you hit an iron shot - your divot always leaves a helpful clue that can tell you a *lot* about your swing. Once you learn to read them, they become a form of instant feedback.

The "Bacon Strip" Divot: The Gold Standard

This is what every golfer strives for. It’s a shallow, rectangular divot that's consistent in depth, often described as resembling a strip of bacon. It begins at or, ideally, just forward of where the ball was resting and points directly at your target.

What it means: You did everything right! Your swing path was neutral, your clubface was square at impact, and your low point was perfectly positioned after the ball. This is the mark of pure compression and a terrific golf swing.

The "Chunky" or "Fat" Divot: The Ground-First Flub

This divot is the golfer’s nemesis. It’s deep, heavy, and starts significantly behind where the ball was positioned. When you take a fat divot, you likely feel a jarring sensation in your hands, and the ball travels a short distance, usually falling far short of your target.

What it means: Your swing's low point is too far behind the ball. This is often caused by a handful of issues: your weight stays on your back foot instead of shifting forward, your arms are trying to "scoop" the ball, or your body isn't rotating through the shot properly.

The "Thin" or Swept Divot (or No Divot at all)

This is the opposite of a fat shot. You might barely clip the top blades of grass or take no divot at all. The resulting shot is hit on the bottom edge of the clubface - often called a "thin" or "bladed" shot - and flies low and hard, running forever when it lands.

What it means: Your swing's low point was either too high or still happening behind the ball. This can happen if you lift your chest or stand up during the downswing (early extension), or if you are consciously trying to "pick" the ball cleanly off the grass instead of hitting down through it.

The "Sideways" Divot: The Path Problem

Pay close attention to where your divot is pointing. A straight divot is great, but a crooked one is a dead giveaway about your swing path.

- Divot points left of the target (for a right-handed golfer): This indicates an "out-to-in" swing path. Your club came from outside the target line and cut across the ball. This is the classic path that produces a slice (if the face is open) or a pull (if the face is square or closed).

- Divot points right of the target (for a right-handed golfer): This signals an "in-to-out" swing path. Your club approached the ball from inside the target line and swung out towards the right. This path often leads to a push (if the face is square) or a hook (if the face is closed).

How to Take a Divot: Your Action Plan

Ready to make better contact and get a satisfying *thump*? Forget about trying to "take a divot." Instead, focus on these fundamentals and let the divot happen as a result.

Step 1: Get the Setup Just Right

Good contact starts before you even move the club. Set yourself up for success.

- Ball Position: For mid-irons (like an 8 or 9-iron), place the ball directly in the center of your stance. This puts it right at the base of your sternum, which is typically the lowest point of your swing if you don't move around too much.

- Weight Distribution: Start with your weight balanced 50/50 between your feet.

- Hands Position: Position your hands slightly ahead of the ball, so the shaft of the club is leaning gently towards the target. This presets the downward strike you’re looking for.

Step 2: Unleash the Lower Body Power on the Downswing, AKA "The Left Shift"

This is arguably the most important element for creating ball-then-turf contact. As you transition from your backswing to your downswing, the very first move you should feel is a slight shift of your hips and weight toward the target (to your left, for a right-hander). This small, subtle move shifts the entire arc of your swing forward, which in turn moves your low point from behind the ball to in front of it.

A great drill: Get a club and take your setup. Swing to the top of your backswing. Now, before unwinding, gently "pump" your left hip laterally towards the target once or twice. Feel your weight shift to your front foot. This is the sensation you want to initiate your downswing with. After a few pumps, go ahead and complete the full swing.

Step 3: Rotational Unwinding, Not All-Arms Action

Too many golfers try to power the swing with just their arms, which often throws the club "over the top" and decouples it from the body. Hitting the ball then making this kind of motion will cause that gnarly slice we never like to use on our scorecard. Think of your body as the engine. The role of your upper body is to unwind - so you can let your golf hips turn freely toward your target. If you do this right, your whole torso should be facing the target at the finish. This keeps your arms connected and promotes a downward strike.

Step 4: Your Secret Swing Thought to Get Rid of Chunk &, Skull Shots Immediately

Don't Be That Guy: A Friendly Reminder about Divot Repair 101

A golf field looks beautiful when it's been maintained, and it's everyone's responsibility to help! Taking proper divots as a golfer is one thing, leaving them unattended is disrespectful to the course and your fellow players.

- If your divot is intact, like a piece of sod, pick it up and gently place it back in the hole, stamping it down with your foot to flatten it.

- If the divot explodes into little pieces, use the sand and seed mix that is usually provided on the side of a golf cart or near the tee box. Fill the hole until it is level with the ground.

Final Thoughts

Taking a divot is not really about digging into the ground, it is the natural result of a properly executed iron shot with a downward strike that strikes the ball first. Understanding why it happens and what it means is all the knowledge you'll need to get better at ball contact and maybe start hitting some really good shots.

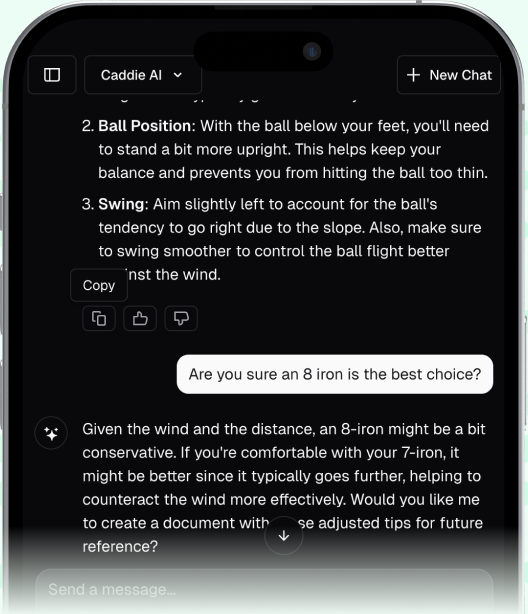

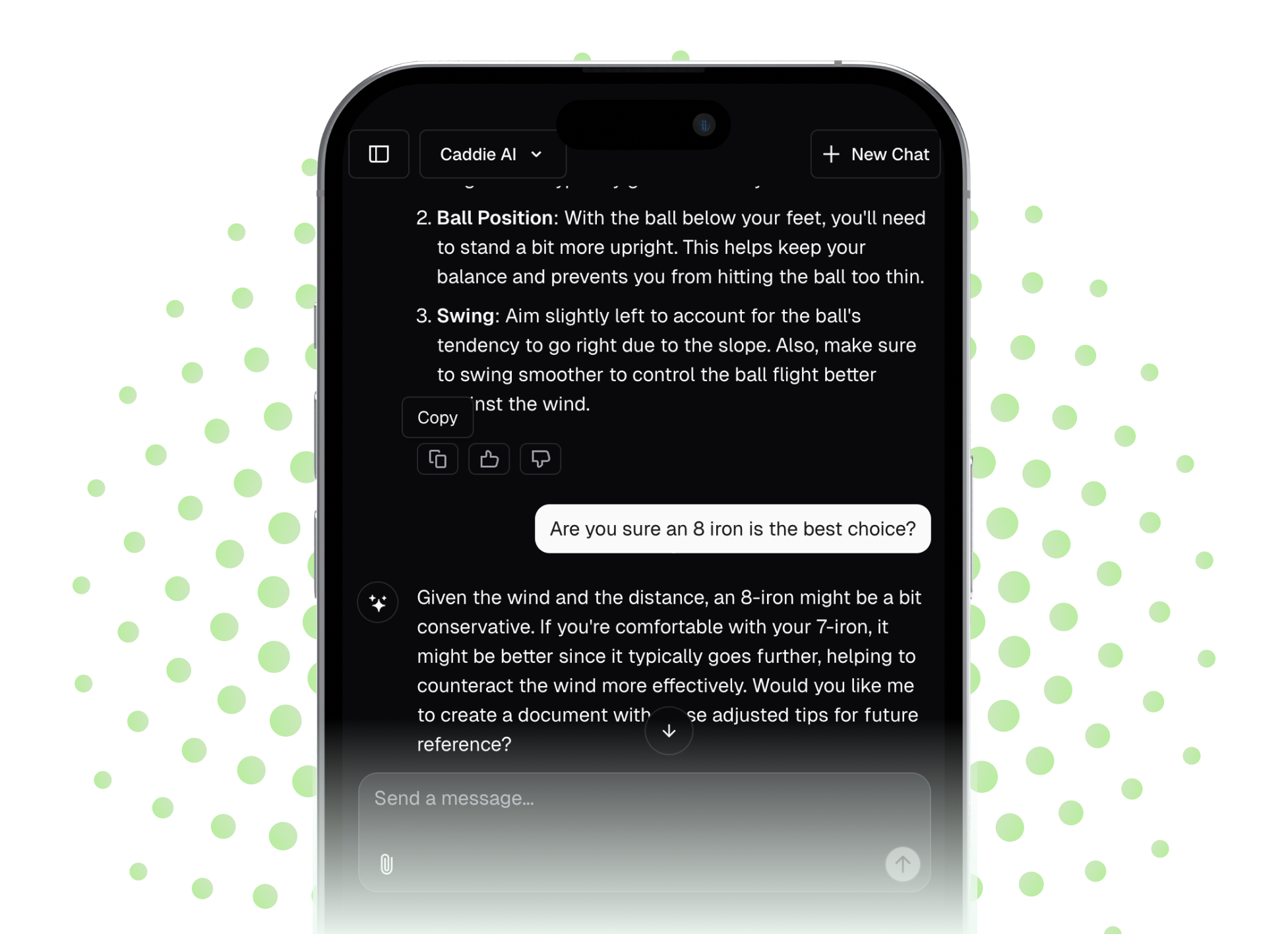

This might all feel like a bit too much to remember while you're trying to swing, and that's where technology can help. With tools like Caddie AI, you don't even have to guess what's going on. Instead of wondering why you just chunked that last shot, you can ask a question for a clear explanation about the low point or even snap a photo of a difficult lie and get instant advice on what to do. Getting personalized guidance on your specific issues means you can turn faulty divots into pure strikes faster and better.