Showing up to your favorite course only to see the greens covered in sandy, grid-like holes is a sight that makes any golfer's heart sink. We've all been there, and the first thought is usually, "Well, so much for making any putts today." But that temporary frustration is the price for season-long putting perfection. This article will explain exactly why golf course superintendents core their greens and how this essential maintenance leads to the healthy, smooth surfaces we all love to play on.

They're Punching the Greens! But What Does That Actually Mean?

When you hear a fellow golfer grumble that the greens have been “punched,” aerated, or “cored,” they're all talking about the same process. It involves a specialized machine that mechanically removes small, finger-sized cores of soil and turf from the putting green. These plugs consist of grass, an underlying layer of organic material called thatch, and the compacted soil beneath it.

Once the cores are removed, they're swept or blown off the surface. The green is then topdressed, which means a layer of sand is spread across the entire putting surface and worked into the holes. This might seem strange - why fill a hole with sand? But this step is fundamental to improving the green's health and playability over the long term.

To really appreciate why this is done, you have to understand what it's fighting against: a combination of soil compaction and thatch buildup, two silent killers of great golf greens.

The “Why” Behind the Punch: Solving a Green’s Biggest Woes

A golf green is a living, breathing thing that endures a tremendous amount of stress. Think about it: thousands of rounds of golf mean tens of thousands of footsteps, all on the same small surface. Add in daily mowing and heavy maintenance equipment, and you have the perfect recipe for problems if left unmanaged. Coring is the superintendent’s most powerful tool for solving these issues head-on.

Problem #1: Relieving Soil Compaction

Imagine trying to grow a houseplant in a pot filled with concrete instead of soil. Nothing would happen. The roots would have nowhere to go, and water would just puddle on top. This is essentially what happens to a golf green's soil compaction over time.

Constant foot traffic and machinery compress the soil particles, squeezing out the tiny air pockets that are vital for a plant's health. These pore spaces are the lifeline for the grass roots. They allow the roots to breathe (yes, roots need oxygen!), absorb water, and access nutrients. When the soil becomes compacted, these pathways are cut off.

Coring is the direct solution. By physically pulling out plugs of soil, the process creates empty channels. These channels break up the compacted ground, allowing oxygen, water, and nutrients to penetrate deep into the root zone. This aids the soil structure and gives the roots the space they need to thrive.

Problem #2: Managing Thatch Buildup

Thatch is the "in-between" layer of living and dead organic matter - old roots, stems, and grass clippings - that accumulates between the green turf you see and the soil below. A little bit of thatch is fine and provides some cushion. But when it gets too thick (more than half an inch), it becomes a major problem.

Think of a thick thatch layer as a waterproof sponge sitting on top of the soil. It can do a few things, all of them bad for a putting green:

- It restricts water flow: During a light watering, the thatch can absorb and hold all the moisture, preventing it from ever reaching the soil and roots where it's needed most.

- It creates a weak root system: Because the water is held in the thatch, the grass roots have no incentive to grow deep. They stay shallow, right where the moisture is, making the plant incredibly vulnerable to wilting and dying during periods of heat and drought.

- It harbors diseases: That overly moist, spongy environment is the perfect breeding ground for fungal diseases that can ruin a putting surface.

Coring physically removes this problematic thatch layer by pulling it out along with the soil. The follow-up step, topdressing with sand, further helps by diluting the thatch that remains. Over years of this process, the soil profile becomes more sand-based, which helps keep thatch in check naturally.

The Ultimate Result: Deeper, Healthier Roots

All of this work - relieving compaction and managing thatch - is done for one main reason: to encourage deep, healthy root growth. When a green has deep roots, it is resilient. It can find water and nutrients far below the surface, making it incredibly tough and able to withstand the stresses of summer heat, dry conditions, and heavy play. That resilience is what gives us firm, fast, and pure putting surfaces for the majority of the season. Without periodic coring, greens would become soft, spongy, and disease-ridden, eventually failing altogether.

The Process and Healing Time

Understanding the "why" is one thing, but knowing the full process helps put the few weeks of bumpy putts into perspective. It's a short-term pain for a long-term gain.

- Punching the Greens: The aerator machine pulls thousands of cores from the green.

- Removing Debris: The grounds crew uses blowers or sweeping equipment to clear all the pulled cores from the surface.

- Topdressing with Sand: A machine spreads an even layer of sand across the green. This is the most crucial step for recovery and long-term health. The sand fills the holes, smoothing the surface and maintaining those channels for air and water. It also helps create a firmer surface over time.

- Healing and Rolling: The sand is then brushed or matted into the holes. Within a few days, the holes begin to close as the turf grows over them. Most greens are back to rolling well within 10 to 14 days, and after about three weeks, you'd never know they were punched. Superintendents schedule this maintenance during optimal growing weather to speed up this recovery process as much as possible.

How to Survive a Round on Punched Greens

While you now understand the importance of aeration, that doesn't make putting on a sandy, bumpy surface any less tricky. So, when you're faced with punched greens, here are a few tips to adjust your game and your mindset.

- Be Aggressive with Your Stroke: Forget "dying the ball into the hole." The sand and holes will slow your ball down significantly. Your primary goal is to get the ball to the hole. Use a firmer, more confident stroke to keep the ball from bouncing offline as much as possible. On short putts, take the break out and hit it straight at the back of the cup.

- Adjust Your Expectations: This is not the day to set a new personal putting record. Accept that you're going to miss a few putts that you'd normally make. Don't get frustrated. Instead, shift your focus. Use the round to work on your striking and short game, and don't worry about the final score quite as much.

- Embrace the Discount: Most courses offer reduced green fees during the aeration recovery period. See it as an opportunity. You get to play what's probably a great course layout for a fraction of the usual price. It's a perfect chance for a guilt-free practice round.

Final Thoughts

Coring the greens, while creating a temporary inconvenience, is the single most important practice for ensuring the long-term health and quality of a putting surface. It's the preventative medicine that fights off compaction and thatch, allowing superintendents to deliver the truest, healthiest greens possible for the rest of the year.

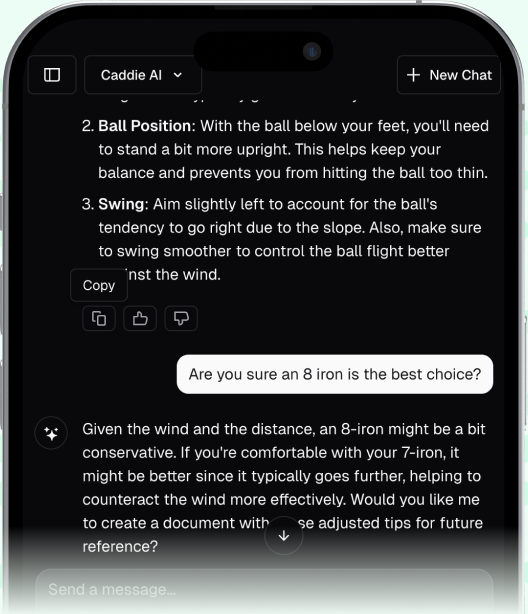

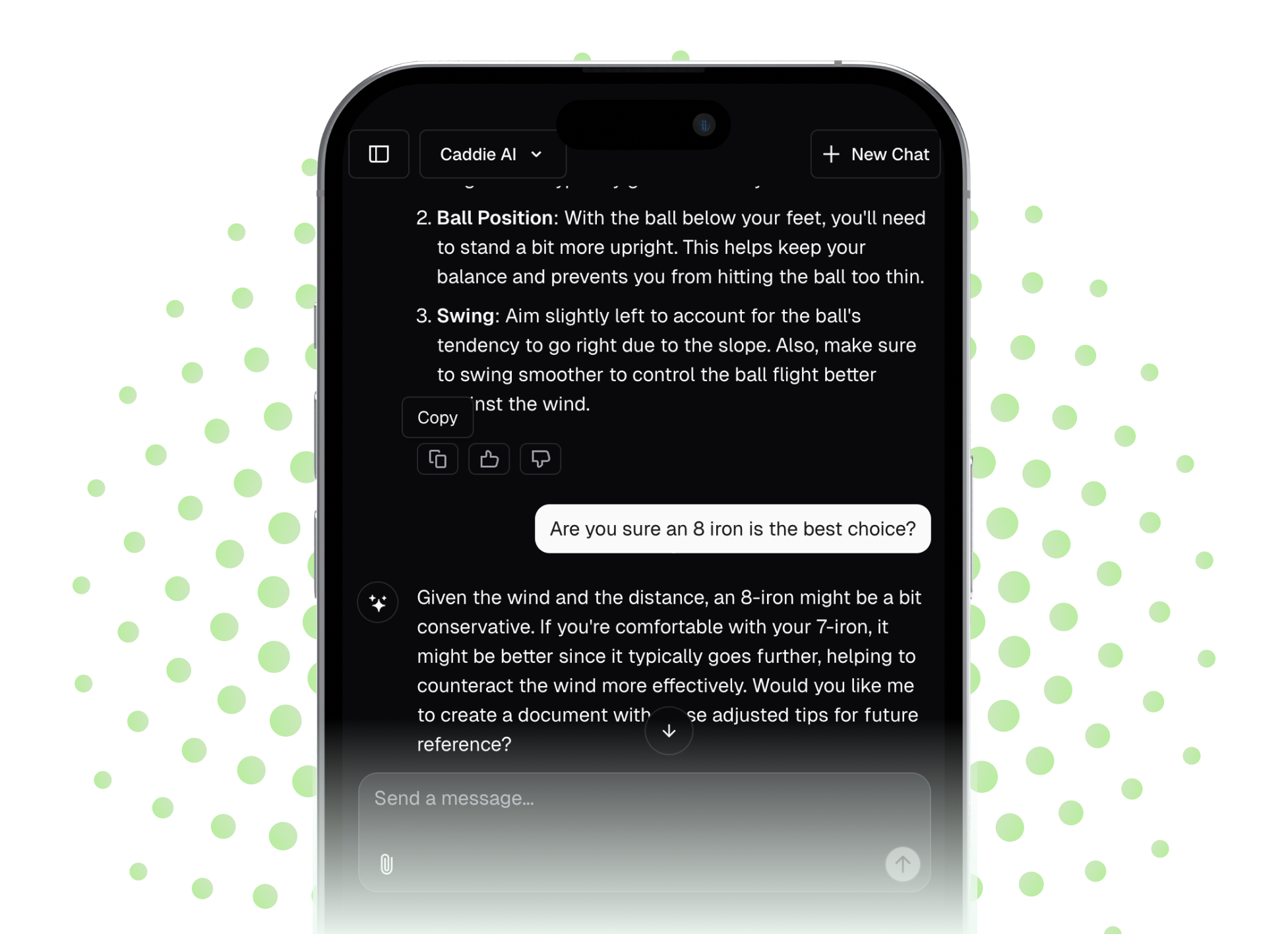

We built our app around helping you navigate the endless variables golf throws at you, from tough decisions to unpredictable conditions. While your putting stroke on aerated greens might be up to you, strategic challenges don't have to be. For any tough situation on the course - like deciding on the right club from a weird lie or how to play a tricky par 5 - you can get instant, simple advice right from Caddie AI. Our goal is to take the guesswork out of your game so you can play with more confidence, no matter the challenge.