Ever watch your playing partners take those perfect, bacon-strip divots after compressing the ball and wonder, Why can't I do that? Instead, you get a clean pick off the turf, or maybe a skull that goes screaming over the green. It's a common frustration, but it's also a giant clue telling you exactly what's happening in your swing. This article will break down why you're not taking divots and give you a clear, step-by-step action plan to start making that pure, ball-first contact that great iron shots are made of.

First, Let's Understand the Divot

Before we fix the problem, we need to know what we’re aiming for. A good divot isn't an enormous crater or a heavy clump of sod. A tour-pro-style divot is a shallow, dollar-bill-sized slice of turf that happens after the golf ball has been struck. This is the most important part to understand: the divot is the result, not the goal.

It's simply evidence of a proper swing sequence. When an iron shot is compressed correctly, the clubhead is still traveling downward when it makes contact with the ball. The lowest point of the swing arc actually occurs a few inches in front of (or on the target side of) the ball's original position. That clean little slice of turf is just what the club collects after compressing the ball against the face and sending it on its way.

So, when you don't take a divot, it's a clear sign that the low point of your swing is either at the ball or, more likely, behind the ball. The club is already on its way up by the time it gets to the ball, resulting in thin, scooped, or topped shots that lack power and spin.

The Common Reasons You're Not Taking Divots (And Which One Is Yours)

There are a handful of common swing characteristics that lead to "picking" the ball cleanly off the grass. Read through these and see which one feels most familiar. Chances are, you'll see yourself in one of these descriptions.

1. The "Scooping" or "Lifting" Instinct

This is, without a doubt, the number one reason amateur golfers don't take divots. It's an instinctive, almost subconscious, move to try to "help" the ball get into the air.

In the swing, this shows up as your wrists flipping and your trail shoulder (right shoulder for right-handers) dipping down through impact. Instead of your body leading the swing and your hands staying ahead of the clubhead, your hands flip past your body, making the clubhead bottom out early. You're essentially trying to use the club like a shovel, when it's designed to work like a hammer driving a nail (the ball) into the board (the ground).

If you hit a lot of thin shots that fly low and hot, or chunky shots where you hit the ground way behind the ball, the scooping instinct is a very likely culprit.

2. Poor Weight Transfer (Staying on Your Back Foot)

A golf swing is a dynamic transfer of energy. In the backswing, you load your weight onto your trail side. In the downswing, you're supposed to smoothly transfer that weight to your lead side. This forward shift is what moves the entire swing arc - and thus, the low point - in front of the ball.

Many players, however, get "stuck" on their back foot. They rotate, but the weight hangs back. When your center is behind the golf ball at impact, it's physically impossible for the low point of your swing to be in front of it. Your body is telling the club, "The lowest point is back here!" The result is typically a sweeping motion where the club comes into the ball on a neutral or upward path.

A good sign you're doing this is if you often finish your swing off-balance, either falling backward or having to take a quick step with your front foot to steady yourself in the follow-through.

3. "Casting" from the Top

Think about a fisherman casting a line. They bring the rod back and then "cast" it forward with a flick of the wrists. In golf, casting is when you unhinge your wrists way too early at the start of the downswing. All that power and lag you stored up on the backswing is released before it can be delivered to the ball.

This early release throws the clubhead out and away from your body, causing the swing arc to become very wide, very early. The club bottoms out miles behind the ball, and by the time it reaches the impact zone, it has to be on an upward trajectory just so you don't dig a two-foot trench. "Casters" are chronic scooping machines because they have no other choice.

If you feel like you have no power despite swinging hard, and your shots lack that compressed "thwack" sound, there's a strong possibility you're casting the club.

4. Incorrect Ball Position

This is a simpler setup issue, but it has a big impact. While every club requires a slightly different ball position, having the ball too far forward in your stance for an iron is a guaranteed way to avoid a divot.

Generally, for short and mid-irons (wedges through about the 7-iron), the ball should be positioned in the center of your stance, directly under your sternum. If you play it further forward, toward your lead foot (like where you'd play a driver), you've moved the ball ahead of where your swing is designed to naturally bottom out. By the time the club reaches the ball, it's already swinging upwards.

This is one of the first things to check - it might be a simple fix that automatically improves your angle of attack. To learn more about proper ball placement, check out our guide on how to position the golf ball in your stance.

How to Start Taking Divots: Your Action Plan

Alright, enough theory. Let's get to work. These drills are designed to retrain your swing and give you the feeling of hitting down on the ball, shifting your weight forward, and making that pure, ball-first contact.

Drill #1: The Line Drill (For Low Point Control)

This is the most direct feedback drill in golf. It immediately tells you where the bottom of your swing is.

- The Setup: At the driving range or on a patch of grass you don't mind marking up, draw a straight line with a tee or place a strip of athletic tape on the mat. Place a golf ball directly on the back edge of the line.

- The Goal: Your only objective is to make your divot appear on the target side of the line. Hit the ball, and then see where the turf is disturbed.

- The Feedback: If your scuff mark or tiny divot is behind the line, your low point is too early. If you hit a perfect shot with no divot, your low point is too high. You know you've done it right when you strike the ball and see a fresh strip of earth removed just in front of where the ball was. Start with half-swings and focus on the feeling of striking down through the impact area.

Drill #2: The Weight Forward Drill (To Stop Hanging Back)

This drill helps correct bad weight transfer by essentially forcing you to get onto your lead side.

- The Setup: Get into your normal setup with a mid-iron. Now, take your back foot (your right foot for a rightie) and pull it back a few inches so only the toe is touching the ground for balance. This should put about 80-90% of your weight on your front foot.

- The Execution: From this setup, just try to hit shots. You won't be able to make a big, powerful backswing, and that's the point. This drill forces you to keep your center of gravity forward and to rotate around your front leg.

- The Feeling: You will feel incredibly stable over your lead foot. Notice how this position encourages your hands to stay ahead of the clubhead through impact, leading to a much steeper angle of attack. You'll probably start chunking it at first because you're not used to hitting down so much - that's a good sign! You're finally getting the club to the ground in the right spot.

Drill #3: The Headcover Hindrance (To Eliminate the Cast)

This drill works wonders if you're a "caster" because it gives you instant, unmistakable feedback if you release the club too early.

- The Setup: Place a ball down and then place a folded towel or an old headcover about one foot directly behind the ball on your target line. It needs to be far enough back that a proper swing won't touch it but close enough that a cast will hit it on the downswing.

- The Execution: Simply make swings. Your goal is to hit the ball without hitting the headcover.

- The Result: If you cast the club, you'll slam into the headcover. To miss it, you must maintain your wrist angles (lag) deeper into the downswing, bringing the club down on a steeper, inside path. This promotes the feeling of "pulling" the club down with your body rotation rather than "throwing" it from the top with your hands.

Final Thoughts

Not taking a divot is almost always a symptom of one core misunderstanding: the belief that you must lift the ball to get it airborne. Once you learn to trust the loft of the club and focus on striking down with your weight moving forward, taking a divot stops being a mystery and becomes the natural outcome of a solid golf swing.

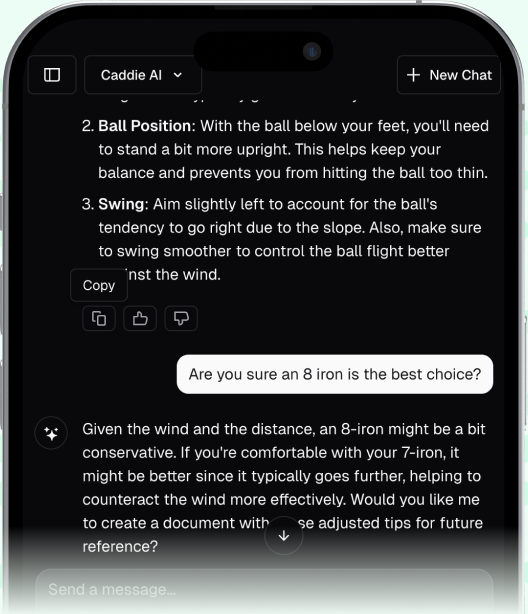

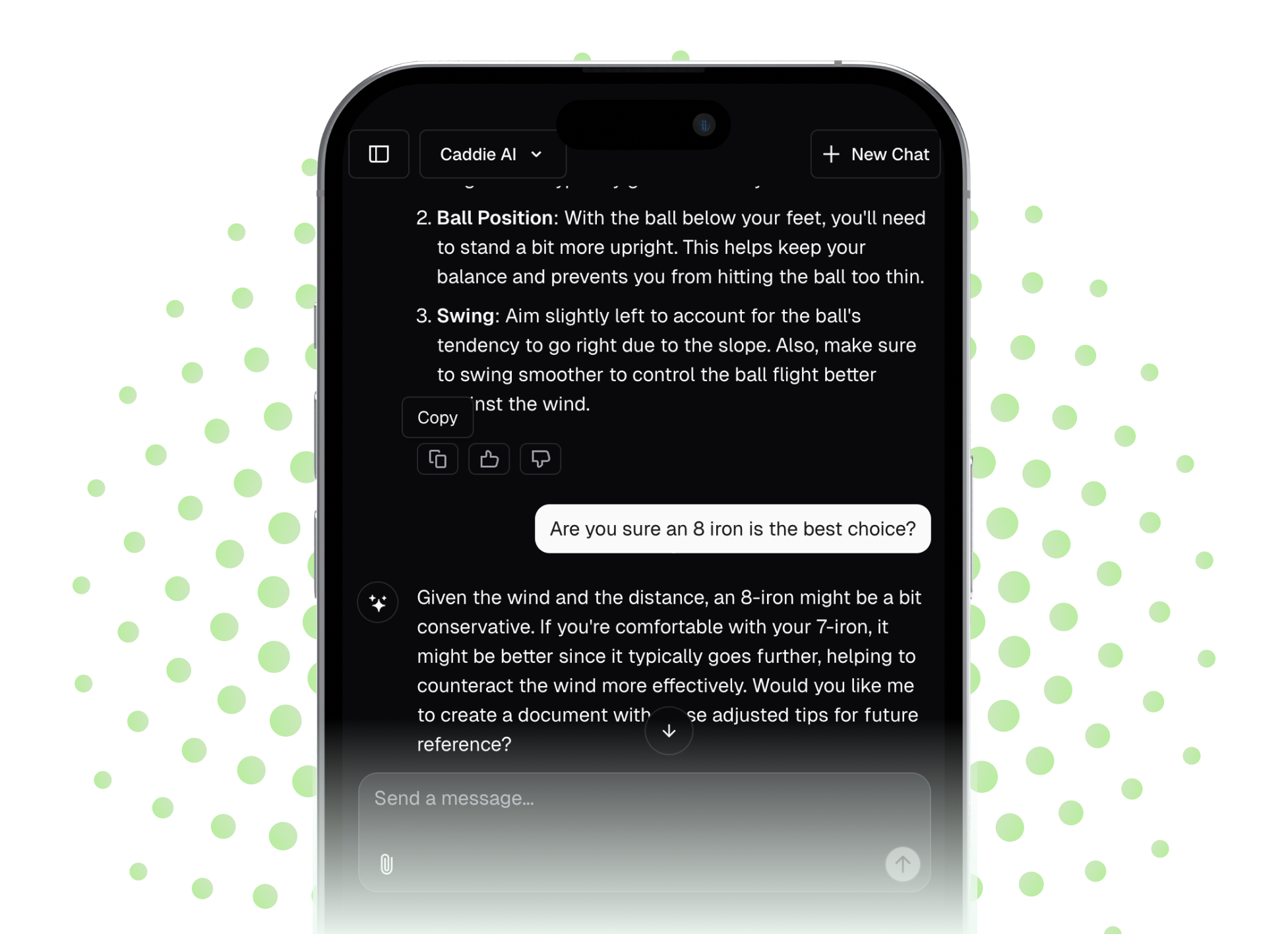

Understanding these faults is one thing, but feeling the correct movement can be tough without a trusted coach by your side. It's what inspired us to create a tool to act as that second set of eyes. With our app, Caddie AI, you can get instant, personalized analysis of swing faults right at the range. If you feel like you are still scooping the ball, you can snap a photo of your impact for analysis or ask for specific drills, getting helpful, simple guidance exactly when you need it most and making your practice time much more productive.