You pure a beautiful iron shot, right off the sweet spot. It feels great. Then, you look down at the turf in front of your ball and see it: a pristine, bacon-strip divot pointing dead left of the hole. If you’re a right-handed golfer, that single clue on the ground tells an entire story about your golf swing. It confirms you have an out-to-in swing path, the number one source of frustrating pulls and power-sapping slices. This guide will walk you through exactly why your divots point left, what swing flaws are causing it, and give you practical drills to get your swing path, divot, and ball flight all tracking straight towards the flag.

What Your Divot Is Meant to Tell You

In golf, it’s easy to get lost in a sea of theories and swing tips. Your divot, however, doesn't lie. It's one of the most honest pieces of feedback you can get. For a right-handed golfer, the direction of the divot tells you the direction your club was traveling at the moment of impact - your swing path.

- A Divot Pointing Left of the Target: This means your club was moving from outside the target line to inside it. This is called an "out-to-in" swing path.

- A Divot Pointing at the Target: This means your club was moving directly down the target line at impact. This is a neutral or "square" swing path.

- A Divot Pointing Right of the Target: This means your club traveled from inside the target line to outside it as it struck the ball. This is an "in-to-out" swing path.

An out-to-in swing path is the root cause of the two most common misses for amateur golfers:

- The Pull: If your clubface is square (or pointed at the target) but your path is out-to-in, the ball will start left of the target and fly straight. A “pulled” shot.

- The Slice: If your clubface is open relative to that out-to-in path, you put slice-spin on the ball. It might start on target or even slightly left, but it will curve weakly off to the right.

If either of those sound familiar, your left-pointing divot is the alarm bell telling you it all starts with your swing path.

The Main Culprit: The "Over-the-Top" Swing

So, what causes this out-to-in path? In almost every case, it boils down to a move known as swinging "over the top." A good golf swing is a rotational action. The club moves in a rounded, circular motion around your body, powered primarily by the turn of your hips and torso. It’s an athletic, unwinding motion.

An over-the-top swing breaks this sequence. Instead of starting the downswing by unwinding the lower body, the first move from the top is an aggressive, lunging motion by the upper body - specifically the right shoulder and arms. This forceful move from the top throws the club outside the correct path. From there, your only option is to chop down and across the ball, creating that out-to-in path and a divot that veers left.

Think of it this way: your body is the engine, and the arms are just along for the ride. When the engine (your lower body and core) starts the downswing, everything flows on the correct pathway. When the arms try to become the engine, they get out of sync and send the club on the wrong route.

Common Flaws That Trigger an Over-the-Top Move

Recognizing the over-the-top swing is half the battle. Now we need to figure out what might be causing it in your setup or swing. Here are the most frequent offenders.

1. Your Setup and Alignment Are Out of Position

Many golfers who slice the ball subconsciously try to correct for it in their setup. To prevent the ball from ending up right of the target, they aim their body - feet, hips, and shoulders - left of the target. While it seems logical, this works directly against you.

When your body is aimed left, swinging straight toward the target line isn't natural. To get the club to the ball and toward the hole, you have to swing across your body line, actively creating the out-to-in path you're trying to fix. You’ve pre-set the slice before you’ve even taken the club back.

The Fix: Use alignment sticks. Lay one on the ground parallel to your target line, just outside your ball. Place a second stick parallel to the first, just inside your heels. Your feet, hips, and shoulders should all be squared up to that line, not aimed at the pin. This ensures your body is set up for a straight swing, not a compensating one.

2. Your Transition from the Top is Too Aggressive

The desire for power often leads to a rushed transition from backswing to downswing. The feeling of "crushing" the ball comes from the arms and shoulders, so it’s tempting to start the downswing by throwing them at the ball with all your might. This is the definition of an over-the-top motion.

A powerful and consistent downswing starts from the ground up. The first move should be a slight shift of pressure into your front foot, followed by the unwinding of your hips. This "unraveling" from the lower body will pull your torso, arms, and club down into the perfect inside hitting position without any conscious effort.

The Fix: Feel the "drop." At the driving range, take your normal backswing and pause at the top. Instead of lunging forward, your first thought should be to let your hands and the club simply drop downwards a few inches toward the ground as your left hip begins its turn. This simple feeling of patience at the top prevents the shoulders from taking over.

3. A "Weak" Grip is Promoting a Compensation

Your grip is the steering wheel of the club, and an improper hold is often an indirect cause of an over-the-top swing. A common fault is a "weak" grip, where the left hand is rotated too far to the left (for a right-handed player), so you can only see one knuckle or less when you look down. This grip position encourages the clubface to fan open on the backswing.

Your brain is smart. It knows that an open clubface at impact will result in a huge slice. So, what’s its subconscious fix? To swing hard from out-to-in (to the left) in an attempt to pull the ball back online. It’s a classic case of one fault causing another.

The Fix: Check your hold. When you grip the club, you should be able to see at least two knuckles on your top (left) hand. The “V” formed by your thumb and index finger should point roughly toward your right shoulder. A neutral grip allows the clubface to square up more naturally, eliminating the need for a compensating over-the-top move.

Drills to Straighten Out Your Swing Path (and Your Divots)

Reading about the problem is one thing, but retraining your body requires repetition. Here are three effective drills you can use at the range to transform your over-the-top move into a smooth, in-to-out swing.

Drill 1: The Gate Drill

This provides immediate feedback on your club path.

- Place a golf ball on the turf.

- Place an object like a headcover or a rolled-up towel about six inches outside and slightly behind the ball.

- Place a second object about a foot inside and slightly in front of the ball.

Your goal is to swing the club through this created "gate" without hitting either object. If you swing over the top, you will hit the outside object on your downswing. If you swing too far from the inside, you risk hitting the inside object on your follow-through. It physically forces you to swing on the correct path to make clean contact.

Drill 2: The Feet-Together Drill

Balance is the foundation of a good rotational swing. This drill takes away your ability to lunge or sway with your body, forcing you to rotate correctly.

- Set up to a ball with a short iron (8 or 9-iron).

- Move your feet together until they are almost touching.

- Take smooth, 70% swings, focusing on staying in balance throughout.

If you try to start the downswing aggressively with your upper body, you will immediately lose your balance and stumble. This drill trains your body to rotate around a stable center point, which is the key to letting the club drop onto the inside path naturally.

Drill 3: The Pump Drill

This drill helps you rehearse and feel the proper sequence from the top of the swing. It breaks the habit of rushing the transition.

- Take your normal setup and swing to the top of your backswing.

- From the top, initiate the downswing feel by dropping your hands and arms down until the club is parallel to the ground. Then, stop. Check your position: the club should be parallel to the ground and pointing down your target line, staying "inside" your hands.

- Swing the club back up to the top of your backswing.

- Repeat this "pumping" motion two or three times to embed the feeling of a proper transition.

- After the last pump, continue the downswing and hit the ball.

Final Thoughts

A golf divot that points to the left is simply an indicator of an out-to-in swing path, often caused by an over-the-top motion born from poor setup or sequencing. By addressing your alignment, building a more patient transition, and ensuring a neutral grip, you can build a swing that approaches the ball from the inside, generating solid contact and divots that point straight at the flag.

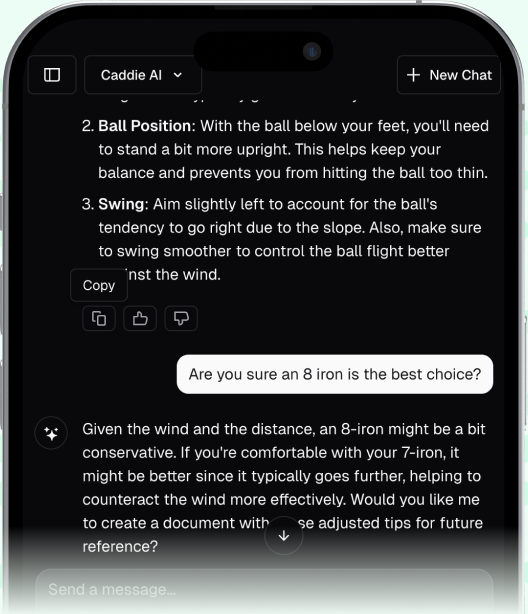

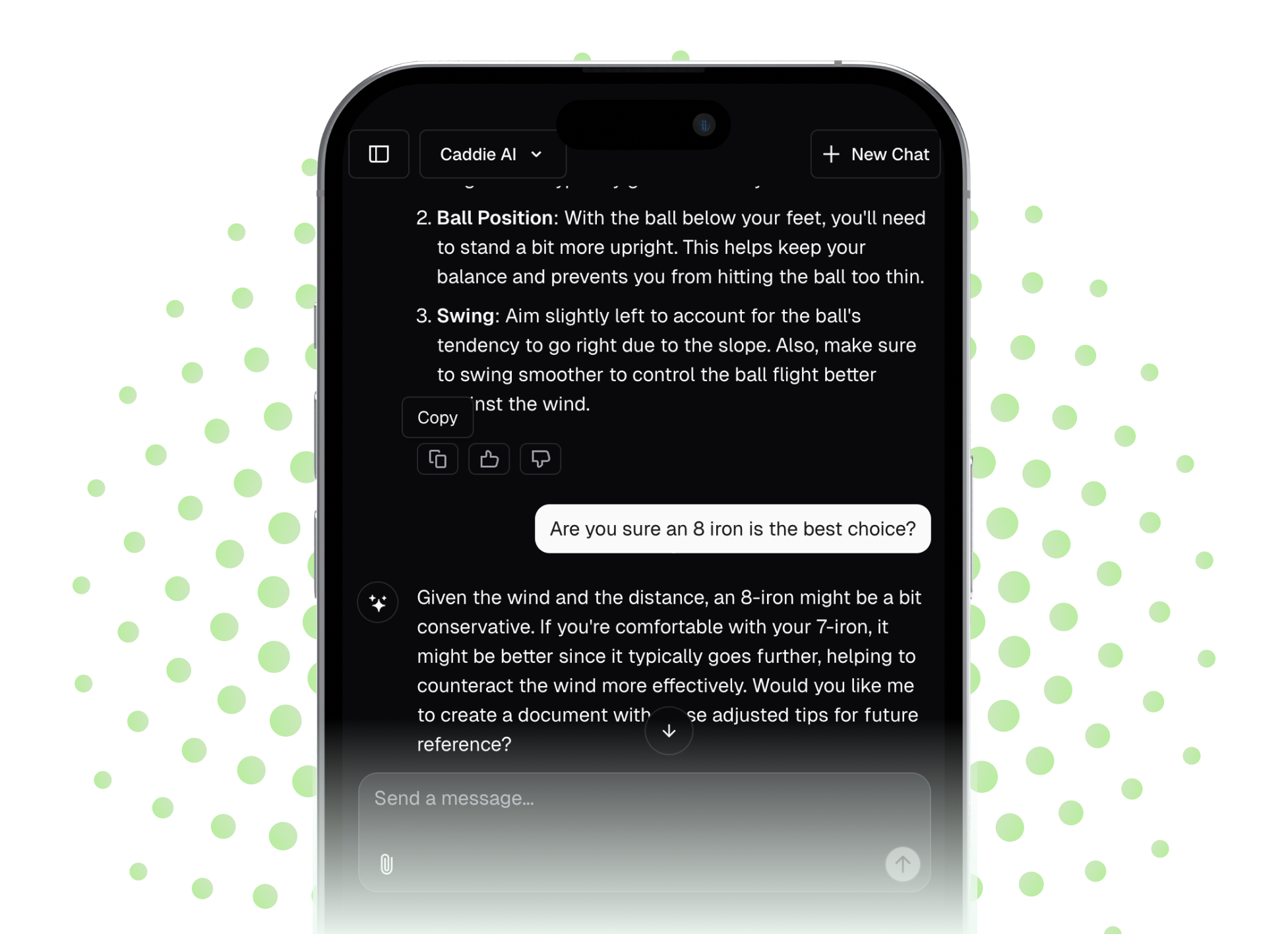

Of course, translating practice feelings to the golf course can be the hardest part. That’s a big reason we developed products like Caddie AI. When you're standing over a ball in the fairway and you start to feel that old "over the top" impulse creep in, you can pull up the app and ask "What’s a good swing thought to stop slicing?" Or, if you’re trying to figure out if your lie requires a special shot, you can even snap a photo of the situation and get instant Tour-level advice. It’s a way to embed good habits by having an expert golf coach right there with you, whenever you need a bit of guidance.